Urchins’ Feast

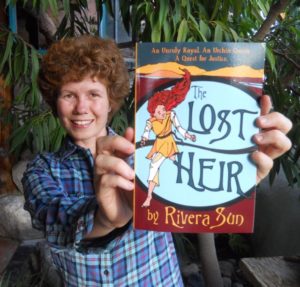

Note: This chapter is excerpted from The Lost Heir: An Unruly Royal, An Urchin Queen, and A Quest For Justice by Rivera Sun. You can purchase the book here. And find the eBook version here.

“No, absolutely not,” the Great Lady Brinelle spoke as she continued reading a draft bill, not bothering to look up at the Ari Ara’s preposterous request. A breeze carried the cool edge of autumn into the study through the open window and ruffled the papers on the desk. Brinelle slammed a paperweight on top of them.

That morning, the young street urchin, Rill, had jogged across the training sands and grabbed Ari Ara’s elbow, her fingers cold with the bite of frost in the air, her cheeks burning bright red with the exertion of the practice. The urchins came in packs to trainings, colorful as autumn leaves as they leapt into the exercises. Rill pulled Ari Ara away from their prying ears as she tugged her jacket back on over her goose bumps. The two girls had been huddled in whispered conversations over the desert silks for weeks; Rill liked the idea, but needed time to work on the other urchins one by one . . . the concept of being allies to the water workers was a thick pill to swallow, even if it was good for them.

“I’ve got most of ’em seeing sense and the rest’ll come around. Now, I hear you’re havin’ a birthday soon,” she remarked with a casualness that didn’t quite cover her excitement, “and I was thinking you could present the silks at the Urchins’ Feast.”

“The what?” Ari Ara asked.

Rill’s mouth dropped open.

“Surely you know?”

Every year on the birthday of the Lost Heir, while the nobles prayed to find the child and mourned the death of Queen Alinore, the urchins threw an enormous festival in the streets.

“Drives the nobles batty, it does,” Rill commented cheerfully, “but we figured the best way to draw the Lost Heir out of hiding was to throw a giant party. Any child with half a brain would come, right?”

The second year, the orphans had joined in, some sneaking out of the orphanages, others let out by sympathetic monks and sisters. The third year, some of the working parents had put out cookies and small cakes on their doorsteps, along with warm winter clothes. From that, a tradition had erupted.

“It’s a grand festival, everyone in the city joins in now,” Rill told her. “Clothes and treats on every doorstep. This year, it’ll be wild with you actually here in the city, found and all!”

Rill stopped and looked slyly at Ari Ara.

“Me and some of the others, we’ve got a bet, though. They says you won’t be allowed to join in, and I told them to stuff their ignorance under a sewer grate . . . of course you’d be dancing in the street with us – how could you not? We’ve been throwing you a party for longer’n some of us has been alive.”

Plus, Rill added, they were friends, weren’t they?

“I told Rill I would go,” Ari Ara spluttered to Brinelle.

“Well, let that be a lesson to you in not making promises that you’re not sure you can keep,” Brinelle replied coolly, lifting up the addendum to the bill and frowning at it.

Ari Ara argued that the orphans and urchins had a special love for the Lost Heir. It would reflect poorly on the House of Marin if she didn’t appear.

“You’ll be spending the day receiving orphans from all over Mariana who have studied diligently and worked hard all year for the honor of meeting you,” Brinelle pointed out, striking a line off the bill and jotting a note on the side.

Ari Ara bit back a sharp retort about being used as a prize to reward favorites and pets. If she could visit all the orphans in Mariana, she would. She knew from personal experience that the most scolded and punished orphans were also the most devout believers in the beneficent powers of the Lost Heir. All orphans of unknown parentage daydreamed about being the Lost Heir and everyone else prayed to the semi-mythical figure. She certainly had, given how often she’d wound up in trouble.

“An orphan,” she told Brinelle in the most respectful tone she could muster, “does not look at the Lost Heir as a reward for good behavior. She cries out to the Lost Heir to help her when life gets tough. She dreams of the Lost Heir appearing and telling her everything is going to be all right. The Lost Heir comes to an orphan as he’s crying with loneliness and tells him his parents loved him!”

She went on, explaining to this rich and powerful woman who had never scrubbed a cold floor on knees that poked through ragged clothes that the Lost Heir’s legend was a special guardian to the children. She had a responsibility to appear in the streets on the night of the Urchins’ Feast. Brinelle straightened her spine and took off the spectacles she’d just begun to use while reading the dense and detailed paperwork from the Assembly of Nobles. This morning, she’d plucked a gray hair from her temple. She looked at the nearly twelve-year old girl standing in front of her desk, blue-gray eyes flashing with temper, pointed little chin stuck stubbornly up in the air, and suddenly, the Great Lady felt old.

“Did I just hear you say the word, responsibility?” she asked the girl, appearing both severe and surprised.

Ari Ara nodded, hoping Brinelle had heard more than that. The Great Lady pinched the bridge of her nose, thinking.

“What did Shulen say?” Brinelle asked her knowingly.

Ari Ara’s body slumped. She crossed her arms over her chest.

“He said it was risky and dangerous,” she muttered.

She’d argued with Shulen for an hour. He told her she’d have to be escorted by guards. She refused; you couldn’t bring the Royal Guard or the Capital Watch to an urchins’ gathering – they’d take off running. Shulen shook his head, his answer was no. Ari Ara told him huffily that she’d take it up with Brinelle.

“Fish will fly before she lets you go,” Shulen predicted.

“I’m sorry,” Brinelle replied, sounding genuinely regretful, “but my answer must be the same as Shulen’s. Someone might try to kidnap or kill you.”

“As if you’d care,” Ari Ara muttered under her breath, a shine of hot tears hitting her eyes.

Brinelle put down her work.

“You may find this hard to believe, but I would be very upset if you were harmed,” she told the girl, secretly appalled that Ari Ara thought her heart was made of such callous stone.

“Why? You and Korin could rule, just as you’ve always planned,” Ari Ara spat out, staring at the floor, kicking the leg of the desk.

A sword blade of anger swung through Brinelle. She took a deep breath and wrestled it down.

“Ari Ara,” she said carefully, trying to not lash the girl with her irritation, “my plan was to advise my sensitive and skilled cousin Alinore as she ruled. My plan was to grow old with my husband. My plan was to find Alinore’s child and put him or her on the throne so that my child could be free of the burden that I have been forced to bear for the past decade.”

Ari Ara started to protest. Brinelle slammed her palm on the desk. Ari Ara flinched.

“Don’t interrupt,” Brinelle snapped. “I have carried this nation on my back, largely alone and often unsupported, for twelve long and difficult years. I swore I would find you and put you where you belong, and that includes keeping you alive!”

Her voice dropped into an icy edge of warning.

“So, no, you may not go to the Urchins’ Feast. You may not realize this yet, but with power comes danger, and you may have enemies lurking among the populace. Ancestors forbid they should knife you, shoot you with an arrow from the rooftops, hire an urchin to poison you, kidnap you and drop you in the Mari River tied to a stone, or any other number of other ghastly murders – ”

“So, no, you may not go to the Urchins’ Feast. You may not realize this yet, but with power comes danger, and you may have enemies lurking among the populace. Ancestors forbid they should knife you, shoot you with an arrow from the rooftops, hire an urchin to poison you, kidnap you and drop you in the Mari River tied to a stone, or any other number of other ghastly murders – ”

“They’d have to catch me first,” Ari Ara muttered, spinning on her heel and stalking out the door.

Brinelle watched her storm away. A faint smile crossed her lips at the girl’s last defiant comment. In a quiet voice, she finished her thought.

” – because, believe it or not, Ari Ara of the High Mountains, I’ve grown rather fond of you for all your temper and rule-breaking.”

[wp_eStore_fancy2 id=36]

On the evening of Queen Alinore’s death and the birthday of the Lost Heir, Ari Ara sat quietly by her window, watching the moonlight turn the East Channel silver. The ceremonies of the day had been long and largely tedious. Tradition held that the Young Queen gave gifts to others on her birthday, so she handed out a staggering amount of objects all day. She sat through a dawn vigil at the temple, honoring her mother’s spirit. She received a long line of nervously smug orphans – the kind of perfectly behaved snots she had scoffed at (and secretly envied) during her short and tumultuous stint at the monastery in Monk’s Hand. At the dinner party with all the nobles, Varina had skimmed within a knife’s edge of accusing her of killing Queen Alinore either by being born or by being part of a plot to steal the throne. The only good part of the evening was when Korin dumped his cake down the front of Varina’s dress and apologized for mistaking it for a wastebasket.

As the House of Marin slowly quieted, a great clamor of celebration rose in the streets of Mariana Capital. When the glow of light from the window in Brinelle’s study dimmed, Ari Ara pulled her oldest training clothes out of her bundle of Monk’s Hand belongings and slipped them on. She’d grown, she realized in surprise. Her wrists stuck out of the cuffs. The worn knees of her pants puckered several inches above her kneecaps. A sense of time and change hit her suddenly. She shook out the folds of her black Fanten wool cloak with its treasured single line of silver hair of elder ewe yarn, smelling the last traces of the scent of the forests and the clear, cold waters of the High Mountains. They’d be gone by morning, the danker air of the river threading into the wool. She inhaled the clear scents one last time, then flung her cloak over her shoulders. The hood hid her bright hair and would make her black against the night. She plumped the pillows under the covers in case a maid peeked in and left a note explaining where she was going. Just in case they did discover her gone, she didn’t want anyone to panic and accuse the urchins of kidnapping her.

Ari Ara threw a stuffed, but light satchel over her shoulder and leaned out the window. The east wall of the House of Marin gleamed in the moonlight. Across the river, the silver-green fields swayed. Below, the stone walls stretched straight down into the murky depths of the East Channel. Pressing her belly flat to the wall, she slid her fingers into the cracks and inched toward the end of the house. After a breathless moment where a chunk of granite broke free under her grip and her other hand slickened with sweat, she reached the corner of the building and descended swiftly. She leapt the last few feet and landed in the alley as lightly as a cat.

Emir stepped out of the shadows. Ari Ara sighed. She should have known.

“The Great Lady and Shulen send their regards,” Emir remarked dryly. “They’re not stupid, you know. They figured you’d do something like this.”

“You can’t stop me,” Ari Ara bristled, trying to skirt around him.

“I’m not here to stop you, silly,” Emir shot back. “I’m here to go with you.”

“What?!” she exclaimed.

Emir told her he’d called in an old debt.

“The Champion’s Boon?” Ari Ara gasped.

Emir nodded. He’d been thinking about it for weeks and finally requested that the Great Lady allow the Lost Heir to join the Urchins’ Feast. It was a gift beyond measure to the poorest inhabitants of the Capital: the urchins and orphans who had sacrificed parents to the War of Retribution and spent long hours of their short lives praying to the legend of the Lost Heir. He understood – even if Brinelle and Shulen did not – how important this was to Everill Riverdon and the other children.

“But – but – to use the Boon,” Ari Ara stammered, honored and amazed, awed by the generosity of her friend.

Emir shrugged.

“It was the least I could do . . . and really, it’s better this way. Thanks to your notorious bad temper, the entire Capital is talking about how you’re not going. It cuts the chances of an assassination attempt in half.”

“Just in half?”

Emir nodded, then grinned cheerfully.

“Don’t worry. I’m sworn to throw myself in front of knives aimed at you. If anything happens, you’ll have the rest of your life to regret causing my death.”

“Thanks,” Ari Ara groaned. “You don’t really think we’ll be attacked, do you?”

“No, and neither does Shulen or you’d be back in the House of Marin already.”

“Things were simpler when I was a nobody,” she complained.

“That’s what Shulen says, too,” Emir informed her. “He said he wished he could just chuck your hot head in the river like he used to when you were just his apprentice.”

Ari Ara laughed. Emir pulled the hood of his cloak over his long hair. Then he pointed to her satchel and asked what was inside.

“A gift for the urchins,” Ari Ara answered simply.

She strode swiftly down the alley before they could be stopped. The streets of Mariana Capital made her gasp in wonder. Emir grinned as she gaped like a wide-mouthed riverfish. Candles had been stuck into carved stone boxes. The doorsteps glowed in every direction. White banners painted with the circle of the Mark of Peace hung from the windows, balconies, and bridges. The black brushstrokes of desert sand and river-water waves rippled in the night breeze. Throngs of children ran through the streets. Every stoop in the Capital was laden with trays of cookies and small cakes. She spotted a door cracking open as a hand extended, replacing an empty platter with a full one. Strips of vintage cloths – gifts for the urchins – adorned the railings. Tied bundles had been placed on windowsills. On the top step of a flight of stone stairs, an urchin bowed his fiddle in a wild jig. Children laid down gifts on the steps at his feet to keep him playing through the night.

She strode swiftly down the alley before they could be stopped. The streets of Mariana Capital made her gasp in wonder. Emir grinned as she gaped like a wide-mouthed riverfish. Candles had been stuck into carved stone boxes. The doorsteps glowed in every direction. White banners painted with the circle of the Mark of Peace hung from the windows, balconies, and bridges. The black brushstrokes of desert sand and river-water waves rippled in the night breeze. Throngs of children ran through the streets. Every stoop in the Capital was laden with trays of cookies and small cakes. She spotted a door cracking open as a hand extended, replacing an empty platter with a full one. Strips of vintage cloths – gifts for the urchins – adorned the railings. Tied bundles had been placed on windowsills. On the top step of a flight of stone stairs, an urchin bowed his fiddle in a wild jig. Children laid down gifts on the steps at his feet to keep him playing through the night.

Ari Ara and Emir ran through the alleys, passing through games of Catch the King and foot races and whirl-in-the-wind. It seemed every turn revealed another musician: pipers whistling out crazy reels, drummers pounding cans and bottles in a cacophony of improvised rhythms, bands of singers bellowing out popular melodies. A pickle organ had even been wheeled out from a tavern to blast its plink-plunkety tunes into the night.

“How will we ever find Rill?” she hollered to Emir over the noise.

“Try the plaza,” an urchin girl yelled back, spinning around when she heard the question.

They shouted thanks and made their way through the street party. The plaza blazed from the bright lanterns hung from the upper stories of the shops. Long ropes stretched into a web across the open space of the square. Buttons on thin thread had been tied to the ropes. Urchins leapt, snatching the round shapes and snapping the threads. Every yank set the rest of the rope lines bobbing, making the other urchins miss their mark. Older urchins put younger ones on their shoulders and jumped so that even the smallest could win a button. Rill perched on the ancestor statue of Marin, cheering on the button-leapers and blowing on a loud horn whenever someone succeeded, setting off whoops and hollers throughout the plaza.

Rill spotted them under their cloaks and teased Emir as they neared.

“You’re a well-built urchin,” she joked. “Ever think of trying for the Royal Guard?”

“We’ve brought a gift,” Ari Ara said, holding out the sack.

“Put that away. Your doorstep’s already the talk of the Capital – or didn’t you see?” Rill answered. “Orphans and urchins are coming back with the history of Marin in antique bands of cloth – the Great Lady must have emptied the museum for us!”

Ari Ara scanned the impromptu armbands wound around Rill’s upper arm. One of the patterns looked familiar and finally she placed it – she’d seen it in a portrait of Brinelle’s mother.

“That was nice of her,” Ari Ara exclaimed, delighted and impressed by the Great Lady’s thoughtfulness.

“So keep your scraps, urchin,” Rill told her grandly. “Tithe’s been made by the House of Marin.”

“Oh, you’ll want this,” Ari Ara answered. “It’s from the other side of the family.”

She held out the satchel and flipped open the top flap. Inside were scraps and pieces of the beautiful pattered silks and colorful weaves of the bolts the Desert King had sent. Each had been rolled or folded carefully and bound with a second bit of cloth to make beautiful gifts for the urchins.

“Urchins’ Ancestors!” yelped a girl sitting on the statue of Alaren next to Rill, looking down in shock. “Is that what I think it is?”

“Desert silk, the finest, straight from Tahkan Shirar,” Ari Ara announced in a loud voice that froze the urchins in their tracks.

“What’s he want?” one lad asked, suspicious.

“Same as us,” Rill called out. “The end of the Water Exchange, and the return of his people and water. This sack is a gift in the spirit of solidarity. He wants his people to come home. We want our honest work back.”

Rill took a scrap from the bag and had Ari Ara tie it around her upper arm next to the fabric from the House of Marin.

“Tell the Desert King that the Urchin Queen thanks him,” she stated grandly, lifting her arm in the air.

A cheer rose up and suddenly, the urchins dove for the silks and began tying them onto their arms. A fiddle struck up a familiar jig. A joyful burst of recognition surged through the urchins and orphans. Rill’s toothy grin bloomed. She slung the precious satchel of cloth over Marin’s sword and ordered another urchin to hand them out fairly. Then she pulled Ari Ara into the fray as Emir dove after them.

“Bet you’ve never seen the Urchin’s Reel,” Rill hollered in her ear. “Try to keep up and don’t worry about the steps – there aren’t any!”

Ari Ara let out a whoop of delight. There wasn’t a dance invented that a Fanten-raised girl didn’t love. At the Academy, she’d had to learn the stiffly somber court dances of the nobles, partnering with Korin to practice the stately steps, but in her opinion, a dance designed to keep extravagant head ornaments in place didn’t stir the blood and spirit like a real dance should.

As a second fiddle picked up the counter melody, the plaza began to writhe with motion. Orphans clapped and joined in with the lyrics – a shocking and humorous account of urchins’ evasions of the Watch. Urchins leapt and hopped, spun and spiraled in a staggeringly chaotic eruption of sheer revelry. Emir kicked out a tap-step from his hills in the north, laughing at Ari Ara’s startled look – he hadn’t always been a warrior, he told her – but his eyes remained watchful.

Rill danced with abandon, throwing her arms high in the air and clapping along with the tune. Ari Ara joined her, setting off a cheerful match of such wild gyrations and astonishing leaps that a space cleared around them. As the second tune snuck in on the heels of the first, the pair didn’t miss a beat. The fiddlers charged onwards, and the two girls strove to out-whirl each other. Emir stepped back into the ring of clapping children and heard the astonished gasp leap out of the throat of a newly arrived young orphan.

“It’s her! The Lost Heir!”

Cheers, whistles, and trills broke out. Smaller children were hoisted up on shoulders to watch. Urchins stood precariously on the stone heads and arms of the ancestor statues. The two dancers laughed. There wasn’t a move either could try that the other wouldn’t attempt. The older children’s eyes shone with emotion. The younger ones hopped in place with uncontainable mirth at the magic of the night.

Emir swallowed down the lump in his throat as he watched the glow rising on the children’s faces. He had seen many things in his sixteen years of life. He had seen the fiercest dedication of discipline under Shulen’s training. He had witnessed a massacre of women and children. He had stopped assassins from killing his best friend. He had beaten warriors decades older than him. He had observed the schemes of the nobles and the extravagances of the wealthy. He had seen dire poverty, famine, and plagues. As a child, he had cried over the battlefields of war.

On the night of the Urchins’ Feast, he saw the best of humanity shining like candlelight in the faces of children. The gleam of joy brimmed in their eyes. Trust and faith returned to the hearts of small children who had known much hardship in their young lives. A glow of wonder gleamed in the faces of youths who had almost stopped believing in miracles.

On the night of the Urchins’ Feast, he saw the best of humanity shining like candlelight in the faces of children. The gleam of joy brimmed in their eyes. Trust and faith returned to the hearts of small children who had known much hardship in their young lives. A glow of wonder gleamed in the faces of youths who had almost stopped believing in miracles.

Yet, a miracle had happened tonight. The Lost Heir had appeared. She was here, dancing, laughing, a child as they were; the lost one, found; returned to those who had held a celebration in her honor year after year, even while the grown-ups warred, mourned, and despaired.

Emir Miresh had risen to fame as the youngest Mariana Champion in a hundred years. He had been awarded honors and medals for his defense of Korin. He had been told many times that his life’s achievements would outstrip even Shulen’s.

Standing in a circle of clapping, cheering children, Emir Miresh knew that no matter what else he did in his life, his choice to use the Champion’s Boon to bring the Lost Heir to the Urchins’ Feast would be the greatest victory of all.

___________

This chapter is excerpted from The Lost Heir: An Unruly Royal, An Urchin Queen, and A Quest For Justice by Rivera Sun.

[wp_eStore_fancy2 id=36]

[wp_eStore_fancy2 id=35]

[wp_eStore_fancy2 id=33]